ERG-RESREP-196 (August 1978)

Scholarly Research in the Academy

A View from Inside

Thomas Lee Eichman

Page numbers from the original manuscript are displayed in the right hand margin

of this document. These may be referenced using fragment identifiers of the form

#pNN, where NN is the desired page number. For example, to

reference page 9 in the original manuscript, use #p9.

Research in librarianship should be able to contribute to establishing

information science as an academic discipline. Librarians, however, may

be fundamentally uncomfortable with or hostile to research. Two recently

published reviews of some of the literature on citation analysis and subject

catalog use reveal assumptions about academic research that conflict with

the author's understanding of its practice.

A theoretical model based on one proposed for information science

by Laurence B. Heilprin is used to explain the author's view of academic

research. This model helps draw attention to similarities and differences

in the intellectual processes of indexing and authoring and to differences

in search and research possibilities afforded by indexes vs. original

documents. The usefulness of citation indexing to the practicing

researcher gains graphic representation. The roles of personal memory

and research comfort demands on the part of a research author are

emphasized.

In conclusion, comparisons are made to applications of similar

iconic models by two other authors, one for documentation and

information processing in general and the other more specifically

for the academic library. Heilprin's work is hailed as helpful

in developing a cognitive view of information science.

Information science may not be well defined as a discipline, but some

fundamental concerns of those persons claiming to be information scientists

are pretty clear. Such persons are largely concerned with the transfer and

storage of knowledge. This makes information science a human science, but

the human is often forgotten in research and applications fostered by

information scientists.

The human factor is fundamental in discussing knowledge in that,

although the transfer and storage of symbols can take place external to

the human, to speak of knowledge requires an assumption of human processing.

Societies that have not developed external storage methods must depend

for the maintenance of culture on the development of elaborate skills of

highly personal storage and transmission, e.g. the griot of West African

radical fame, a phenomenon found generally in pre-literate cultures, as

in the oral tradition that may be the basis for Homer's poetic works.

In modern societies which have developed more or less elaborate external

symbol storing devices, it is easy to forget that the individual human

possesses an elaborate internal device for storage and that most if not

all persons make use of that internal device, called the memory, in their

daily work, be they laborers or scholars.

The longest standing tradition of external storage is that which

transfers knowledge into a written representation on an external, smooth

surface. The transfer of knowledge from one human to representation on

an external surface and then back from that surface to another human has

traditionally been called writing and reading. In the beginning it is

clear which came first; something had to be written before anything could

be read. The general beginnings of writing and reading are so remote,

however, that for most people who read and sometimes, if at all, write,

it undoubtedly is axiomatic that reading should come before writing.

An elite group of persons, research scholars and literary artists, knows,

however, that the sources of inspiration for creating written texts are

not necessarily other written texts. The creative process is an internal

process not very open to external observation and evaluation. Only its

products, in the case of writing, composed texts, are generally open for

close inspection.

Academic libraries serve the scholarly tradition by providing storage

and assisting in the transfer of knowledge, and have done so for many

years. With this long tradition, librarianship ought to be able to provide

a basis for the development of a more comprehensive discipline concerned

with transfer and storage also in less traditional forms, i.e. an all-encompassing

information science. However, modern librarianship appears

not capable of articulating its own tradition well enough to be able to

contribute in a general way. Librarianship seems to be looking too much

to outside sources to explain its own behavior.

Modern librarianship does have a good understanding of the storage of

knowledge, especially in the traditional written form, and seems to be

finding it easy to apply this understanding to storage in non-traditional

forms. Traditional librarianship also understands apparently fairly well

half of the transfer of knowledge, from storage to recipient. But the

other half of the transfer, from creator to storage, appears to be almost

totally misunderstood and in large part misconstrued by traditional

librarianship, at least in the more modern representatives of it.

In a general critique of librarianship, Paul Wasserman sees a general

inadequacy in research in the discipline and attributes it to librarianship's

pragmatic basis:

[R]esearch in librarianship is viewed largely as the gathering of

facts to support political decisions in individual situations. The

intrinsic resistance, symptomatic of the entrenched professional

preference for its own tradition, relates perhaps to a view that

research may threaten the existing order. If pragmatic librarianship

rests on certain assumptions and if the consequence of research may

be to cast doubt about these very tenets, here is where risk lies.

To encourage, to support, or to believe in research is to tolerate

ambiguity — the possibility that there may be other viable alternatives,

that existing practice is not divinely inspired. The net effect is

a profession which is not only uncomfortable with the idea of research.

but fundamentally hostile to it. [1, p. 142]

The discomfort or hostility that Wasserman perceives may extend to research

generally, thus contributing to librarians' misapprehension of the creative

scholars and artists who produce and use the knowledge stored symbolically

in libraries.

Further below I make clearer some of my own specific criticisms, but

I wish, first of all, to profess my belief in the value of service provided

by modern librarianship to the academic scholarly community and to express

my optimism about the role librarianship might play in guiding information

science into becoming an academic discipline. If its practitioners, who should

have a lot of valuable experience, would only look at librarianship more carefully

and state clearly and forcefully what it does and does not do, they could,

I feel, create the basis for a discipline of information science.

Introspecting and scrutinizing about librarianship is a rather large

and difficult task if one is trying to make sense of the entire picture.

I will not attempt here to give a description of the whole scene or to

provide fundamental definitions, code words, keywords, etc. as a basis

of a theory of library and/or information science. I will try, in a rather

limited way, to account for a few aspects of academic library and document

use with which I am personally familiar but which seem not to be well

understood by many who have written about them from within the library

world. For my purposes I make use of an explanatory model proposed generally

for information science. In another article I have used this model, with

slight modification, to help account for an aspect of library work which

I felt I understood from the moment I first encountered it, but which was

incomprehensible to most librarians, or so it seemed from the library

literature I read about the phenomenon. [2]

The information science model I have used and use here is based on

one developed by Laurence Heilprin in references [3], [4], [5], [6], [7],

[8], and [9]. The choice of models is a personal one, since I was influenced

directly in its study by Heilprin himself. My applications of it, however,

depend on its usefulness in explaining certain things. The model and

the theory behind it have been built very carefully over a period of years

and depend on general physical and psychological theories for support.

One test for any theoretical model for a discipline is how well that

model accounts for aspects of that discipline. This paper is meant as a

partial test of Heilprin's model. If it convinces others, I hope that

they might test this model in other ways. If nothing else, I hope my

discussion here will cause others from within librarianship to think about

our discipline in a new way.

One aspect of scholarly research that appears to be very puzzling to

librarians is the meaning, nature, relevance, and further usability of

bibliographic citations found in, under, and after the text of reports

of research, published in journals, technical reports, books, and various

other forms of documents. One mistaken view I find common to librarians

is that such citations are somehow separate from the rest of the document

in which they are found. This view often comes out in discussions of

citation indexing and citation analysis and is especially revealed when

someone questions the applicability of citation studies or statistics to

some practical aspect of librarianship. For example, one eminent practitioner

of the art of applying the computer to library processes speaks of

"bibliographies attached to published papers." [10, p. 146]

As a researcher, I usually find that a list of publications at the

end of any report I read can be very useful. I often will make a copy of

such a bibliography without necessarily copying the whole work, but usually

only after I have found that the publication in which it is contained says

something important to me as a researcher. I even find that later I may

make a completely different use of the list than was my original intent,

so that such a list can have separate existence and use. Saul Herner [11, p. 33]

reports a similar phenomenon in the reaction of someone else to the

references in a study he had prepared. Most of the time such a list

is most useful to me, however, in conjunction with the text of the document

in which it is found. In this regard it is the references made in the

text, or the footnotes to the text, citing those works which may be found

listed at the end of the text, that make the citation of those works and

the works themselves useful in my research — neither the text alone nor

the references alone but all together.

Another aspect of the research use of bibliographic references apparently

not well understood among librarians is the seriousness of intent behind

their inclusion in a research publication. This may be just a variation

of the mistaken view that separates the references from the text. Nonetheless.

it does appear also as a direct question in discussions of the use of

citation analysis in supplying library services to the academic community.

In a fairly recent review of some of the literature of citation analysis,

the reviewer, a library school faculty member, comes to the conclusion,

"References (citations) do mean a great deal. Fears that they are made

carelessly or for ulterior motives are not justified by evidence presently

available." [12, p. 328] These 'fears' were apparently the basis for some of the

studies reviewed by Broadus and logically must still exist for many

librarians, since Broadus attempts to lay them to rest with these concluding

statements. His next statement, following the one cited above, has

practical implications for librarians, "A high proportion of readers

depend on references as leads to other publications — more, apparently,

than make use of indexing and abstracting journals."

One of the implications, especially for more general libraries, such

as those found at universities and colleges, is that it is a "proportion

of readers", perhaps even a majority, but at least not all readers, who use

references as their primary way of getting into the literature. This means

that one vehicle cannot be made to serve everybody. Nonetheless, Broadus'

proportion does include me as a reader and, I believe, many other academic

researchers to a very high degree. Herner also notes this phenomenon

and makes an even finer distinction, commenting on an older study in which

he was involved, "Pure scientists, who spent the most time in libraries

and made the most use of published literature, made much less use of

library reference and bibliographic services than applied scientists,

who made less physical use of libraries and of published materials than

pure scientists," [11, p. 33]

Reports of research, especially the more valuable ones, are creative

in what they report. The difference in what is crested makes a difference

in the two types of document usage and style of retrieval noted by Herner.

Michael Polanyi comments on the creative difference insightfully:

The beauty of an invention differs . . . from the beauty of a

scientific discovery. Originality is appreciated in both, but in

science originality lies in the power of seeing more deeply than

others into the nature of things, while in technology it consists

in the ingenuity of the artificer in turning known facts to a

surprising advantage. [13, p. 178]

Because the pure scientist, to use Herner's terms, is concerned with deep

penetration of nature within a community of scholars with a specific

tradition, he must not only observe the natural things around him and

reflect on them but must also read the reports from others in order to

make a claim to originality in his own reports. Obviously, it benefits

both the pure and the applied scientist to read reports and gain from the

experiences of others, but the orientation of the applied scientist, or

technician, can account for his seeming lighter regard for the primary

literature and heavier use of fact-finding vehicles. Polanyi goes on to

make the point:

The heuristic passion of the technician centres therefore on his own

distinctive focus. He follows the intimations, not of a natural

order, but of a possibility for making things work in a new way for

an acceptable purpose, and cheaply enough to show a profit. In feeling

his way towards new problems, in collecting clues and pondering perspectives,

the technologist must keep in mind a whole panorama of advantages

and disadvantages which the scientist ignores. He must be keenly susceptible

to people's wants and able to assess the price at which they would be

prepared to satisfy them. A passionate interest in such momentary constellations

is foreign to the scientist, whose eye is fixed on the inner law

of nature. [13, p. 178]

The pure scientist's heuristic passion may be towards the inner law of nature,

but he also has a distinctive focus, very personal to him, but also very cognizant

of other scholars in his discipline. There are also momentary constellations

in pure science, usually of a discipline's superstar researchers and their associates

and the reported findings of such groups. These constellations guide others

in their fields far beyond their personal knowledge. The research stars may be

productive, influential, and gleam brightly for a long time, or they may burn

out quickly after an initial flash or warm glow.

Wasserman's point about the pragmatic basis of library research can

be accommodated in the distinction between pure and applied scientists,

or scientist and technician, except that Wasserman makes the stronger

claim that librarians are afraid to invent new applications. Indeed,

there are more and less creative applied scientists, just as there are

more and less creative pure scientists.

The creative applied scientist who wishes to profit directly from

his discovery must pay careful attention to the literature of his field

in at least one way similar to a way that the creative pure scientist does.

The patent literature search, as is well known, desires most strongly a

truly negative finding, i.e. that the idea does not exist in the literature.

Part of the motivation for the pure scientist to read as much as he can in

his field is to find a similar negative result in the scientific literature

about some idea of his. The staking out of claims within science has been

discussed before [14], but I would caution anyone from attributing it as

the sole motivation of pure research. The territorial imperative is only

one possible explanation for the publishing of significant research findings.

Some humans like to share territory, ideas, and many other things also.

Broadus' study is a fine example of research for applied library science.

The rest of the text in his summary and conclusions following the paragraph

I have strung out above is devoted to a discussion of the implications of

the results of his findings for the applications indicated in his title.

His report affords the opportunity for occurrence of one of the phenomena I

described earlier. The references listed at the end of Broadus' report

make a great jumping off point into the literature of citation analysis.

Especially valuable are Broadus' evaluative comments within his text on

each individual item when laid alongside the original item. The works

Broadus cites and discusses themselves can lead into other works found

cited in them, and an ever expanding network can be built up which can be

cycled into the future through the established citation indexes. One could

probably go on forever reading material related in some way to citation

analyses and studies of citation behavior.

In the library world, pragmatic as it is, constructing theories of

library use that are predictive of events to come should be one important

goal of library research. It is my impression that there has been a

burgeoning of studies of library use that have revealed a multitude of

findings about the behavior of humans in libraries. Theory beyond the

immediate applicability of these findings even sometimes creeps into the

reports of those studies. It is at such times that the attitudes that

underlie library practice are often most revealing.

There is one stimulating study of the use of subject catalogs which

started out as a library school doctoral dissertation [15] and which has

been reported on more recently in two journals [16, 17]. The conclusions

reported in the dissertation include the betrayal of an assumption about

the nature of academic research that I think is common among librarians

but which conflicts with my understanding and practice of it. The study

is based on a survey of some of the literature of catalog use and on a

laboratory study done by the author in a state university system. The

assumption with which I disagree lies behind the following statements:

It appears . . . that knowledge of the subject content of a field does not improve

one's success rate [in the use of pre-coordinate subject headings for

retrieval of books]. Apparently, variations in knowledge level of

a subject do not affect success. This seem unjust, somehow. It

is not proposed that a system be designed where users are penalized

for ignorance, but on the other hand, experts should have their searches

eased by their knowledge. In the chapter 1 review of other studies in

this area it was noted that subject catalog use appears to slack off

as the user rises on the academic ladder. It was surmised that this

decline in use might be due to the increasing dissatisfaction of the

user with a system not geared to the expert. There is nothing wrong

with serving the novice in a field, but the expert (including the

undergraduate major) working in his own field should not be badly

served. He is, after all, the primary client of a university or

research library. [15, pp. 227–228]

In the summary and conclusions of one of her articles [16], Bates shows

that she has thought more about this assumption; there she poses a few valuable,

provocative questions that should be considered within librarianship.

Nonetheless, this article still includes a general assumption about the

use of the library catalog which views it as the one vehicle through which

users get into the literature stored in the library. The assumption is stated

most directly in the introduction [16, p. 161], "In one sense, the catalog is the

crossroads of an information facility. It is where the user starts searches

of all kinds .... The catalog is where . . . the user interfaces with the

information store", and is restated in the second article [17, p. 367], "The

catalog is the principal information access device in most libraries and

information centers."

The searches of 'experts', at least of the scholarly researchers of my

acquaintance, do not ordinarily begin with the subject catalog. Indeed, it is

hard to tell where and when scholarly searches as a part of research begin, or

where they end, for that matter. The simple search probably started far back

in time for the advanced researcher and was no doubt part of a general search

for a subject to major in as an undergraduate, a status from which he was next

lured into graduate research for very personal reasons of interest.

In an excellent introduction to the study of anthropology, which has

advice that graduate students in any academic field would do well to heed,

Morton Fried, in discussing undergraduate training in his discipline, says,

[T]he student begins to perform research functions when he follows

an author's work (or a small portion of that work) to its sources

as revealed in the author's footnotes and bibliography. At the same

time, the student should be looking for the critical reviews that

were published about the book, or, if it is an article he is examining,

he must try to find out if it struck some response which would usually

appear in a later issue of the same journal, or might be revealed

in one or another bibliographical index. [15, p. 116]

It is my belief that 'experts' do have their searches eased by their

knowledge. For a very good reason not having to do with inadequacy of the

vehicle, academic researchers rarely use the subject catalog or the simpler

forms of subject guides as the starting point to the literature in their

narrower fields. The reason is largely, I believe, that most scholarly

researchers have a personal history of a longtime habit of reading as much

as they can, no matter where or how they find it, on rather narrow subject

areas. Their reading habits may extend to doing a lot of reading outside

their fields also, but their most intense disciplinary knowledge is well

defined, in their minds at least.

Part of this personal knowledge of a field is a memory of what is

written where and when and by whom. There is an intense attachment to

names and dates within their areas of interest. Researchers come to

associate certain names, certain journals, certain publishing companies,

certain academic and other research institutions, rightly or wrongly, as

the case may be, with certain topics and subtopics within their narrower or

broader ranges of interest.

When such researchers want to find something they have seen before,

they either know where to look or have other ways than just through the

subject catalog to go about finding it. When they are looking for something

new, they know which journals might publish something thought provoking to

stir new interests. They also know which publishers are putting out which

new books about the subjects they like, in part through advance advertisements,

which may be in the journals or on dust covers of the books they buy and

read, or which may come to them through a system of select dissemination of

information by means of the professional junk mail coming from those publishers or other

bookdealers who have pulled their names off one or another elite list,

usually the membership lists of professional societies or subscription lists

to professional journals.

Academic researchers usually know which shelves in their favorite

libraries are likely to have new books of their liking appear on them

occasionally because they have probably visited those shelves quite frequently,

especially in open-shelf, self service systems. They also know how to recognize

a new book on an old familiar shelf. These abilities to recognize new

items in familiar display areas and to know which areas to look in to find

fond items may be viewed as an extension of general human abilities as in

the ability for shoppers to recognize items among the products on display

in a favorite shopping area and the ability to know which shops to look into

for the kind of item desired. Many a scholarly researcher can be found

passionately stalking the shelves of libraries and bookstores.

The scholarly researcher also knows there are more ways than one to

skim a catalog. He may even go to the subject catalogs and indexes on

occasion, especially if he is starting off into a new field of interest or

going back to one he has not looked at for some time and for which he has

forgotten the layout. But I firmly believe that librarians should not see

as a failing on their part the fact that ‘experts' do not use their subject

catalogs all that extensively.

Subject catalogs do have failings in form, as I have experienced

intensely in attempts as a neophyte general reference librarian to help

undergraduates get started into the literature of fields I am not personally

familiar with. But I think it would be a mistake to gear the efforts of

correcting whatever failings there may be to an attempt to make subject

retrieval devices more useful to all experts. Scholarly experts will use

those devices only occasionally.

Even if it can be shown to the researcher that his research does not

yield all the possible documents he might use, he will probably reject any

outside attempts to force more material on him. He knows what he likes and

where to get what he likes. If he does not know precisely where to look,

he knows he can experience again the fun part of research that comes from

uncovering something himself. Gerard Salton hits on the attitude of

scholarly resentment to outside intrusion in his description of reactions

to the selective dissemination of information:

By far the most common complaint of SDI users appears to relate to

the large volume of output continually delivered by the services.

Even if the proportion of relevant items is fairly high, users

receiving 30 or 40 citations every week will soon tire of the system

and will revert to on-demand searches which furnish output only when

a specific request for service is actually on hand. [10, p. 147]

It is a truism of American society that many people dislike too much junk

mail, even if sometimes it may prove interesting and useful.

In the review of user studies in one of her articles, Bates [16, p. 162]

reports again, "There is considerable evidence that as users go up the academic

ladder, they tend to use the subject catalog less and less relative to the

author-title catalog," a conclusion with which I obviously agree. She goes

on to assert, "No user studies were found that investigated why this trend exists."

I have already offered informal remarks meant to help explain the trend Bates

perceives. I will proceed now to attempt to account more formally for the

academic researcher's use of scholarly references.

In my attempt I use the model mentioned in my introduction. My discussion

is not based on controlled laboratory observation of overt behavior. It is

directed at fostering an understanding of behavior evident through Broadus'

and Bates' reviews and which I know is a part of the nature of academic

research as I have practiced it — and have observed others practice

it — in my experiences over the years as a graduate student at three

major universities, dissertation writer, teacher of undergraduates at two

campuses, author of journal articles, independent researcher, and part-time

university general reference librarian.

As stated in the introduction, the theoretical model I use is based on

a model found in the various writings of Laurence Heilprin. His most concise

presentation is in [9, pp. 25–29, plus figures 4 and 5]. Versions publicly more

accessible are in [3, pp. 298–302], [6, pp. 23–29], and [7, pp. 120–128].

Heilprin's statement of theory is based in part on communication theory

that has been developing for some time and uses an iconic model of the process of

communication much like those that communication theoreticians have been

using since at least the time of Shannon and Weaver. There are two ends

to the communication model, one end sending, the other receiving. In

between is a channel for communication. To connect the two ends there must

be some means of encoding and decoding the message to be sent and received

through the channel.

One of Heilprin's contributions to the discussion which makes his

theory and models important in the library world is his emphasis on the

individual at either end. Libraries are very personal means of communication.

Users usually approach quite individually and personally the messages that

libraries assist in transmitting. The symbolization of an individual at

each end of the communication channel intensifies this assumption in the

applications to which the model can be put.

A second and, I believe, very important contribution Heilprin makes

with his theory is a distinction between long and short duration messages.

The most obvious short duration type occurs in face to face or electromagnetically

assisted interpersonal real-time situations. This type, the

length of duration of which is a function of the medium, usually sound, light,

and/or electromagnetic waves, and of the distance between originator and

recipient, has been the concern of most of the communication theoreticians

who have developed similar models to explain communication behavior. This type

message of short duration is important in a library, especially to public

service librarians who must facilitate information transfer to individual

recipients, e.g. in reference negotiation. In reference [2] I have used

Heilprin's model as part of an analysis of interpersonal short duration

messages occurring at the beginning of library reference encounters.

The long duration message is the kind that is stored in some

body-external medium, resulting in what is commonly referred to as a

document. The long duration messages that a library assists most in transmitting

have their origin in what is commonly called an author and are stored

in book, journal, manuscript, film, record, and various other forms. By this

theory also, some of the body-external tools in the library that aid in the

search for certain stored messages are themselves stored messages that started

with someone authoring them, e.g. a cataloger or indexer, and resulted in

inclusion in a body-external documentary form, i.e. a catalog or index.

In this analysis, as Heilprin goes into in some detail, the stored

document's message can be read only by an individual at the receiving end

of the communication model and then only when the application of some external

energy is appropriate for the conversion of the markings of the stored

message into similarly patterned short duration messages. That is, pages

must have light shine on them, films must have light through them, and vinyl

disc records must have power to rotate them for the groove-tracking stylus

to do its symbolic dance of minute proportions, so that the messages symbolized

on the pages, films, and discs can be discerned by the person wishing to use

them. At the storage stage, the energy has gone into preparing a message for

long duration, normally involving short duration movements in fixing the

storage medium.

The symbol for the individual at either end of Heilprin's model

includes three body-internal parts, one for receiving messages, one for

sending them, and, between these afferent and efferent organs, a center

to process them, which in some philosophical and psychological traditions

is called the mind. I believe Heilprin's symbolization of the integral

individual communicator with internal processing is very important, because

it has the effect of saying that not all of the activity important in

understanding the human use of libraries is behavior which is externally

observable or which can be derived just from the observations of external

behavior without some very strong assumptions about the internal character

of the individual producing the behavior. It is a methodological assumption

which is quite different from the behavioristic assumptions behind many of

the user studies reported in the library literature. Behaviorist psychology

has had a strong challenge to its assumptions from linguistics and other

cognitive based research in the last twenty years. I believe it is time for

shining the light of cognition on library and information science research.

I agree to a great degree with Victor Rosenberg's opinions about the premises

of information science, [19] and [20], and I believe Heilprin's insightful

model can provide the necessary starting point for new vision in our field.

For this paper I confine the discussion to long duration messages,

that is, those found stored in documents of one form or another, with the

assumption that these must be converted into short duration messages for

sensing to take place. For my purposes I have made a few modifications of

Heilprin's model of the communication process.

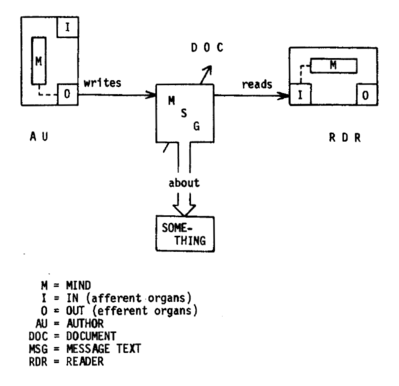

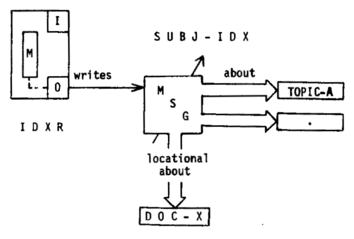

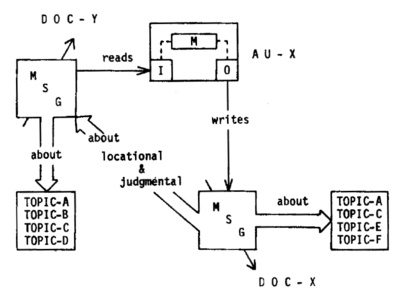

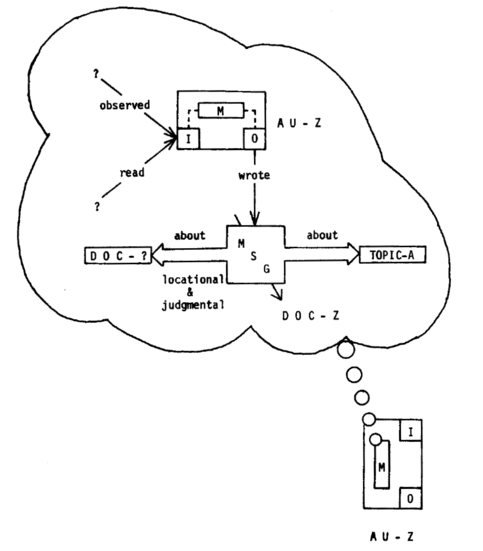

My basic model is presented in figure 1. The rectangles at either end

represent individual humans. The areas marked I, O, and M stand for the

bodily internal IN-organs, OUT-organs, and MIND, respectively. The IN-organs

are any sensor or set of sensors humans possess. For the purposes of this

paper they will be mostly the eyes used in ordinary reading, though they

could be the ears for listening to sound recordings, the fingers for Braille

reading, or whatever other body parts for whatever other means humans have

of sensing externally stored messages. The OUT-organs would be mostly the

fingers using pencils, typewriters, etc. for written documents but could be

whatever other organs that might be used in controlling body-external,

medium-fixing instruments. The MIND is the mind and for the purposes of

this paper will be assumed. Any attempts at describing it here could lead

into a lengthy and discursive philosophical, psychological, and physiological

sideshow using lots of other Greek-based words and symbols. Its assumption

is useful in what follows; its assumption is valid in many circles of the

Western tradition of cultural analysis. Neural connection between the mind

and the mind's body-internal tools is acknowledged by the broken line from the

MIND portion to or from one of the organs at the extremities.

The originating body in my model is marked AU in a traditional library

abbreviation for author. The person at the other end of the process of

transferring the stored message ls marked here in a general form as RDR,

standing for reader, but it should be understood to represent anyone

distinguishing, recognizing, and making sense of the patterns emanating from

the message stored in the document, which in general form in figure 1 is

marked DOC. The lines of communication symbolized by the single line arrows

marked writes and reads and connecting DOC to both AU and RDR can be interpreted

most generally to stand for the creation and understanding of externally

stored messages by humans, whatever the means used.

The single line arrows outside the bodies show the direction of the

external flow of the message. The use of the slanted arrow within the DOC

symbol is an adaptation of Heilprin's symbol for indicating a variable time

delay from creation to understanding through the deferred sensing that is

possible with messages of long duration. The text of the message is symbolized

inside the document as MSG. I mean by this symbolization to assert that the

document is to be distinguished from the message text, even though in the

stored form they may appear to be nearly the same thing.

Just as a document contains a message, so does a message have contents.

Although a message and its contents also may appear to be the same thing,

they must be kept distinct. The contents of the message are symbolized in

my model by another unit outside the DOC symbol. The contents, however,

do not exist inside or outside the message except through the minds of the

AU and the RDR. Grasping this aspect of symbolic communication has been a

stumbling block for some communications researchers. I symbolize the

connection here by means of a double line arrow which is meant not to imply

that it is leaving the message but to show that the message in some way

relates to its contents. Including the label about with the double-lined

contents arrow is intended to help symbolize the indirectness of this

relationship. The addition of an about arrow comes from another model of

the communication process by Geoffrey Leech [21], whose analysis is based

in part on the functional analysis of Roman Jakobson [22]. It is the only

structural change I have made to Heilprin's basic model, the rest of my

modifications being essentially changes in labels.

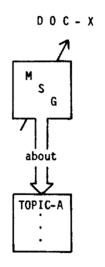

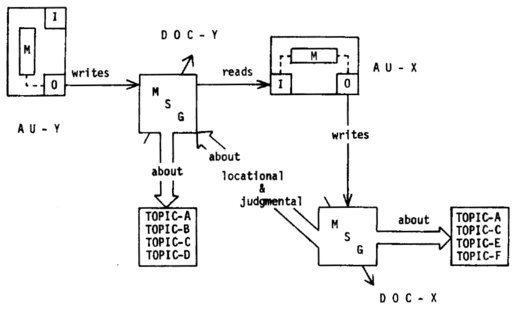

In figures 2a and 2b I have abstracted two views of a document from the

stored communication model of figure 1. The view as in 2a is easy to arrive

at from the point of view of a library or other information storage area.

The book, the journal, the film, the sound recording, even the computer

tape, is an object that lies or stands on a shelf or in a drawer, or otherwise

takes up space, and is quite tangible. With a little reflection, however,

the next figure, 2b, is not hard to keep in mind, especially with books

that emblazen their creator's name in gold or other pretty decoration on

their spines, or with the journal article whose author's designation is

displayed in generous white space just below its own name, the article's

title. The Anglo-American cataloging tradition has canonized the practice

of author recognition in its general principles for catalog entry [23, pp, 9–10].

Both figures 2a and 2b disregard the contribution of editors and

publishers to the form of the document, but the documents themselves, and

in part the rules for documentation, do make more or less explicit recognition

of at least the publisher responsible for the form of the document. Researchers

usually recognize the processes that stand between the creation of a message

and the storing of it in documentary form. They cannot but have become

acquainted with the processes as producers of some of the documents that have

come to be stored.

Perhaps this is the first part of the definition of a researcher, someone

who has created a message stored somewhere in a document, as contrasted to

searchers, persons who may have handled documents extensively but have never

gotten a message stored in documentary form. The American Ph.D. tradition

canonizes this distinction by making the granting of the research degree

dependent on the depositing of a documented message, the dissertation, in at

least one storage facility, the degree-granting institution's library, then

often to be made more generally available through on-demand reproduction,

a process with which the dissertation's author may be personally familiar

because of degree requirements to provide a copy for microfilming, to pay a

microfilming fee, and to produce an abstract of the dissertation to be used

in advertising the work to other researchers. Whatever other documents a

researcher produces — books, journal articles, and various other forms of

research reports — usually go through several stages of editing, printing,

and publishing, which themselves become very apparent to the researcher

transmitting messages through those processes.

Because researchers generally understand that there is often a great

deal of work that must be done between the time an intellectual work first

gains physical form as a manuscript by an author and then gets stored in a

library as a document, I have subsumed all the intervening processes under

the single arrow marked writes. This is not intended to discredit editing

and publishing, but only to draw attention to the creative aspect of authoring,

an aspect of research which, I believe, is not generally understood by librarians.

Librarians may have a personal acquaintance with some of the publishing

aspects of the preparation of a message for storage through their contact

with publishers and their wholesalers at the selection and acquisition stage

of document storage. The processes of library selection and acquisition may not be

well known to researchers, but the purpose of this exposition is to explain

researchers to librarians, not librarians to researchers.

One potentially misleading aspect of my model is the delineation of

TOPIC's in the contents portion of the stored message. In documents of

free text, e.g. typical books and journal articles resulting from scholarly

research, the topics discussed in the messages of those documents are usually

not so easily delineated as my symbols might suggest. I intend to use a

single enclosure around all the topics in a stored message as in figures 2a

and 2b to indicate that the topics are included within free text. Some

documentalists use the term 'natural language' for this distinction, but I

my attachment to that compo1compound's designation in the traditions of philosophy

and linguistics disallows my use of it here. The term 'free text' as I use

it is potentially misleading also. I hope the distinctions I am trying to

make here will become clearer in the later portions of the present text.

The various topics in free text may be more or less separately discernible

by a reader. The reports emanating from different traditions may lend themselves

more or less readily to mechanical elucidation of topics through the calculation

of occurrences of words. Those disciplines with rather rigid jargon and

quite stern, even ossified traditions of style in communication, e.g.

jurisprudence, secret military correspondence, may lend themselves more

easily to mechanistic text analysis, but a general method of such abstraction

of topics by keywords seems not readily realizable for the purposes of

scholarly research. The hard part of using a document for research comes in

reading its message, discerning the intended meaning, and fitting the

understanding gained from that reading into whatever else is going on in the

mind of the reader. Librarians who may or may not do a lot of reading of

separate texts may be misled on this point of topic analysis because of the

forms of messages that they deal with a great deal, i.e. indexes, abstracts,

and other condensed and/or simplified subject statements.

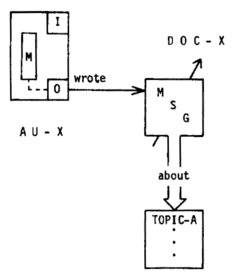

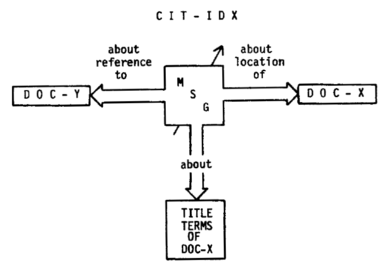

In figure 3 I have represented a static view of an index. The two-fold

array of double-lined about arrows attempts to capture the functioning of

a subject index, here meant to include many types of subject indicating

devices, e.g. the subject portion of a library's card catalog or the various

subject indexes with which the many reference librarians are more familiar

than I am. A subject index typically lists a series of short statements

each made up of a word or word group or other symbolization of a series of

topics more or less precisely selected, depending on the characteristics of

the index, and then gives clues to the location of documents whose messages

contain something about the topics so represented.

Even though I have symbolized the topics referred to by the index's

message as individual items in figure 3, i.e. TOPIC-A, etc., it should not

be forgotten that this is not meant to indicate that this is the form in which

a reference to TOPIC-A, etc., is necessarily found in the index's text, but

rather that a portion of the text of the index‘s message is about TOPIC-A, etc.

Nonetheless, indexes, with their typical unitary symbolization tend to give

the impression that TOPIC-A is the words or other symbols standing for TOPIC-A.

To understand why this is not the case, think of the very general topic

'water'. In an index, I could symbolize this with the English word water, or

the German word Wasser, or the chemical notation H₂O, or even some non-standard,

arbitrary notation such as Kg78*-444. As long as the reader of those symbols

understood the system of notation, be it common language or special symbols,

the topic would be understood to be the same. It is, however, quite easy

to forget that the reference to topics is through symbols if you use quite

frequently an index that has as its notation words from the common language.

Despite the potentially misleading character of my unitary symbolization

for topics in an index, I prefer to use it as in figure 3 for the aboutness

representation of an index's message, because enclosing each topic separately

makes a convenient, and, I believe, revealing contrast with the free text

representation I have symbolized in figure 2. It should not be forgotten,

however, that the form of the symbols for TOPIC-A, etc., is within the text

of the messages about the topics, and that the text, whether created by an

author or an indexer, only represents TOPIC-A, etc. Recognition of the problem

of fitting words or other symbols to concepts is rather basic to the use of

reference tools. Devices to aid solution of this problem include thesauri

and other means of vocabulary control.

Indexes have creators, something that readers, even librarians, too

easily forget or do not even realize. It is easy to look at the entry in a

card catalog or other standardized index and forget that some person has,

at some point in time in the past, created a message contained in that

entry. A more complete view of the index, in the sense that 2b is a more

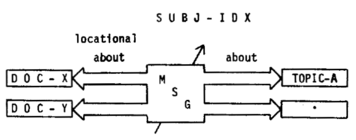

complete view of any document than is 2a, is contained in figure 4a.

Here I have included, for simplification of the diagram, locational

reference to only one document. With figures 3 and 4 it should not be

forgotten that an index may include locational reference to many more than

one document with each reference to TOPIC-A, etc. The simplification

incorporated in figure 4a is due to the representation in the next figure,

4b, which is intended to symbolize the process by which an indexer creates

a message for storage in an index about the topics of a single given document,

which, if I understand the human process of indexing, is the way its progress

is measured, document by document, even though the indexer may he working

on more than one at any one time and in the end summarizes the process by

collecting together all the documentary references to TOPIC-A, etc.

Figure 4a might have left the suggestion that the indexer just makes

up indexes out of his head, but in fact, except perhaps for spurious

examples, indexing requires some effort at examining the document being

indexed, symbolized in 4b by the reads arrow. To make the communication

process from original author through the indexer to the stored index even

more complete, I have added the AU symbol and his writes arrow to get

figure 4c, much as I added the personal and creative symbols to get 2b from

2a and 4a from something like 3.

I think 4c is a better way to symbolize subject indexes, not only

because it is a completer statement of the processes behind their creation,

but also because it symbolizes elements related to a document that are

usually found in indexes used in libraries. Not always, but usually there

is indication of the author along with the locational information of a given

document. Other information, especially usually the document's title, is

included with the locational information. All of this documentary information

about the message being indexed could be specified more explicitly along

with the cover term locational which labels the double-lined about arrow

connecting the index message to the original document. I wish, however,

to subsume all that documentary information under the one term, and I believe

it will not be too misleading to do so. Generally, indexes are pretty clear

in references to documents and their locations. although the actual practice

varies and can be confusing, e.g. In the use of abbreviations for 'well-known'

journals.

In figures 4b and 4c the contrast between the message texts of researched

documents and the simpler texts of indexes referring to them, utilizing

the symbolic variations for the representation of TOPIC-A, etc. as discussed

above, becomes important. Say that a person is searching for material on

TOPIC-A and has stumbled onto or been guided by a librarian or other

resourceful person to an appropriate subject index symbolized as in figure 3

or one of the variations of figure 4. Suppose that such a searcher has

correctly discerned that the message of the subject index contains reference

to TOPIC-A as being located in DOC-Y. Following from this there is a naive

view that when our searching person gets to DOC-Y he should quite easily

locate the portion of DOC-Y that refers to TOPIC-A, and, most naively,

should also find there in the text of DOC-Y the words which the searcher

found in the text of the index's message used for describing TOPIC-A.

I think what I have described as a naive assumption about message texts

is quite common among persons not having much experience in scholarly

research, which may be another way of saying not having read a lot of free

text in depth about a topic, a possible step in defining a scholarly

researcher, by saying what he is not. It may well be that certain texts

or types of texts allow for a simpler minded searching approach. Such

may especially be the case with documents meant to serve fact finding.

Fact-finding information gatherers may look at their index map and go into

the library woods tn gather their information berries, but that is hardly

an adequate way to describe a vast portion of scholarly research.

Scholarly research does include writing and reading, but it also

demands thinking. Subject indexing meant to serve scholarly research must

also include some thinking. This aspect of indexing is symbolized as a

potential of the MIND portion for the IDXR in the variations of figure 5.

Finding reference to DOC-Y in a subject index is only one way of getting

to DOC-Y. Another way to get there is to come across DOC-Y directly, which

may appear to he harder to do than to go through the subject index, especially

if the reason for getting to DOC-Y is to find something about TOPIC-A.

However, knowledgeable researchers do have other means, a large number of

which involve indexing of some kind, although it may not be the kind that

results in a stored message of the type found in a subject index.

Shelf arrangement is a well known device for indexing and retrieving

documents by means of general classification. Browsing is a well discussed

topic and is also a functioning part of my method of research. However,

browsing, in its most productive form, which I would prefer to call shelf

searching, is an active process that depends on the searcher having done a

lot of reading before going to the shelves, although not necessarily

immediately before, and also some careful reading while at the shelves.

Thinking is also very much involved, and so may be writing, to the extent

at least of making small notes if, for example, the active shelf-searcher

comes across a document he cannot take along at the moment.

In addition to external classification devices, an active researcher

has categorized in his mind the journals, publishers, books, etc., that

are likely to have material about TOPIC-A, if indeed the researcher is

familiar with that topic as a part of his discipline. As the reading,

thinking, and writing of a researcher intensifies, and perhaps also broadens,

the researcher becomes very expert, not just about TOPIC-A, but also about

the form of documents, and, most importantly. about specific documents

that have discussion of TOPIC-A from several points of view.

Different researchers may employ very different and very idiosyncratic

methods of keeping this documentary information in their files and/or minds,

but it is generally true that an advanced researcher has well developed

means of keeping tabs on what is published or being published about the

topics in which he is interested.

I do not intend here to describe elite groups of highly paid researchers,

such as those in medical, space, and secret intelligence fields, who are

given what seems to an outsider as unlimited funds, part of which they can

spend to develop elaborate electromagnetically interconnected retrieval

devices using gross operations of mindless machines. Those researchers

have their own methods, including a lot of yes-men-and-women to carry out

factory-like information assembling tasks. With large numbers of people

and machines between researcher and message store, different things happen

than with a more or less independent researcher who goes more or less

directly to the stored message.

I intend to describe here also more than just the elite groups of

researchers commonly known as 'invisible colleges'. What is designated by

that phrase, which has been used as an appellation in English speaking areas

for more than three centuries, is the very personal way that rather select

groups of individuals have of keeping each other informed of what they and

the other 'important' people are doing. Members of an 'invisible college'

are usually highly visible to anyone who has followed a particular discipline

that can be said to have an 'invisible college'. Only their privy secrets

remain unseen beyond the fold until someone decides to display them in public.

Usually there is enough leakage to enable anyone exerting a little effort

to figure out generally what is going on within the group.

I mean, in addition to members of the visibly elite, to include among

scholarly researchers the common garden variety Ph.D. holder who reads a

lot, thinks too, and writes, although maybe he does not get what he writes

into 'documentary' form very often. Such people abound in colleges and

universities across the United States. The largest portion of their writing

may be in the form of lecture preparation notes and as advisory notes to

term papers and/or tests from students in classes they teach. These people

are not so highly visible on a national scale as are the members of the

‘invisible colleges', but they can be observed in lots of places, essentially,

or hopefully, wherever there is an institution that considers itself one

of the academies of higher education. The names and credentials of some of

them can he found listed in the various volumes published under the Jacques

Cattell imprimatur, e.g. Directory of American Scholars, American Men and

Women of Science.

In a way, this very large group of certified researchers provides,

through the courses they give and the relationships they develop with students,

a very valuable link to the research that goes on nationally. These academic

leaders form the final funnel for much of the information of a 'higher'

nature that trickles down to the students in such academies. This is

especially so if, as I think to be the case, many undergraduates read very

little, and then only what has been assigned by their instructors. Because

this group is readily perceptible, if one only looks in the right place,

but also because the individuals in this group are not so clearly distinguished,

a designation for them as a whole may well be 'the translucent college'.

These very important people do read a lot and arrive at documents

through other means than through subject indexes supplied by librarians

and other information handlers. The kind of independent researcher I have

in mind may well get to a document through reference to it in another

primary document. As many user studies have shown, this is quite commonly

the way an experienced reader follows a topic through documents, especially,

I believe, the reader conducting research, hence doing a lot of reading.

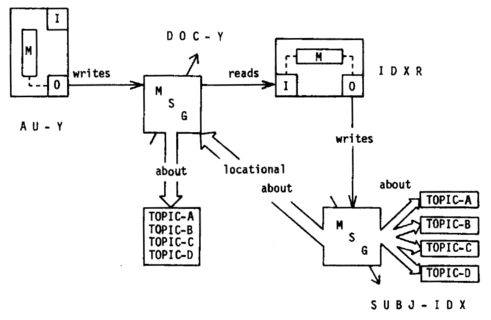

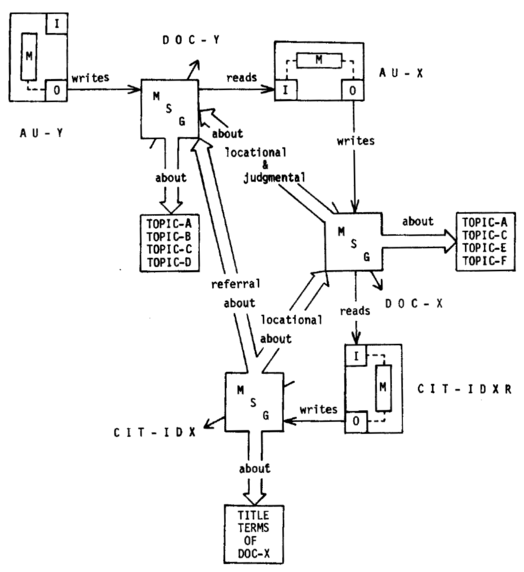

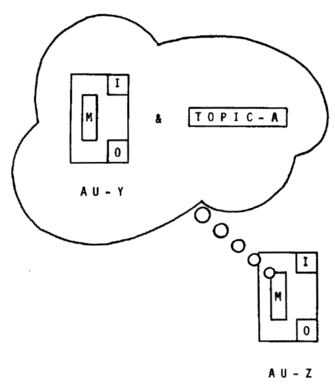

In the three figures of 5, I symbolize the writing, reading, and

referring research processes once again based on the Heilprin-Eichman

model of stored communication. As before, I show the various states of

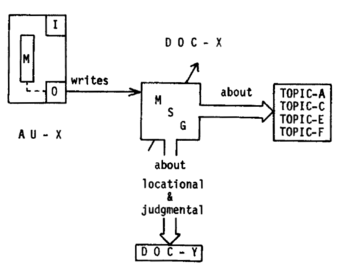

completeness of view of the processes of reading and writing. Figure 5a

already has an author symbol attached to a new DOC-X, which contains

reference to DOC-Y. Figure 5b adds the reading that AU-X must do to be

able to make reference to DOC-Y, and 5c completes the picture by designating

as AU-Y the originator of the message contained in DOC-Y and used by AU-X.

Notice the outward similarities between the models of the indexing

process in in 4a, b, and c, and that of the process of authoring in 5a, b, and

c. Notice that both in indexing and authoring a person writes a new

message that refers to his reading of DOC-Y. The referral to the location

of DOC-Y within the text of each type of document, in the index and in the

second document, DOC-X, will be fairly similar in form, since participants

in search and research processes, indexers and authors, more or less agree

on style of documentary reference. However, the message of DOC-X will often

differ in its reference to DOC-Y in a way very fundamental to the research

process from the standpoint of a person wishing to read DOC-Y for further

research. As indicated with the inclusion of the phrase judgmental along

with locational on the double-line about arrow connecting DOC-X to DOC-Y,

there is, more often than not, I believe, either an implicit or explicit

value judgment made about an original document in the message of another original one citing it.

Another important difference between a subject index and a referring

document as with DOC-X is the manner in which TOPIC-A is dealt with in the

text of each. As we have seen before in discussing the representation of

the references to topics found in indexes, it is easy to view TOPIC-A as

the words that stand for it in the message text of the subject index. In

whatever way it is that an indexer decides that DOC-Y contains something

about TOPIC-A, he will generally symbolize it with a concise symbol or

group of symbols. When one looks at the text of DOC-Y, one may or may

not find the symbol or group of symbols the indexer has used to symbolize

TOPIC-A. If the indexer has done a good job, then other people reading

DOC-Y will agree that it contains something about TOPIC-A. To prove the

thoroughness of the indexing of DOC-Y, one has to find agreement that

in addition to something about TOPIC-A there is also material about TOPIC-B,

TOPIC-C, and TOPIC-D in DOC-Y, i.e. all the subject statements the indexer

has assigned in indexing the document.

A simple-minded searcher coming to DOC-Y looking for something about

TOPIC-A and coming across material that is about the other topics as well

may think that the indexer has done a sloppy job of categorizing the text

of DOC-Y, a trap I often find myself falling into on those few occasions

when I use a back-of-the-book subject index in a book in one of my specialty

fields. A less simple-minded view would acknowledge that TOPIC-A is

included in DOC-Y along with the other things found discussed there and

would assume, or at least would probably hope, that the indexer had seen

the total picture also and had captured the essence of the document with

the topic statements he chose. I believe that a lot of people who use

subject indexes as their main tool for access to research literature do

hold a more simple-minded view similar to the naive view of representation

I have described above.

In figure 5c (and 5a and b also) I have symbolized the contents of

DOC-X with different topic statements than those for DOC-Y, oversimplifying again the aboutness

relation of the text thereby, but also hopefully stressing the difference

between a second, referring document and an index. The difference in form

between topic statements in the document's text and the index's text is

indicated by enclosing the topics of the second document within one

rectangle as a message unit as opposed to the separate rectangle for each

topic statement of an index as in figure 4c. It might be good to recall

at this point the static view of the subject index as in figure 3. A

subject index covering both DOC-X and DOC-Y would list all the topics in

both documents and make references to the appropriate documents with each

topic reference. In the case where there is sharing of topics, e.g. TOPIC-A

TOPIC-C, the index will make reference to both DOC-X and DOC-Y with each

shared topic.

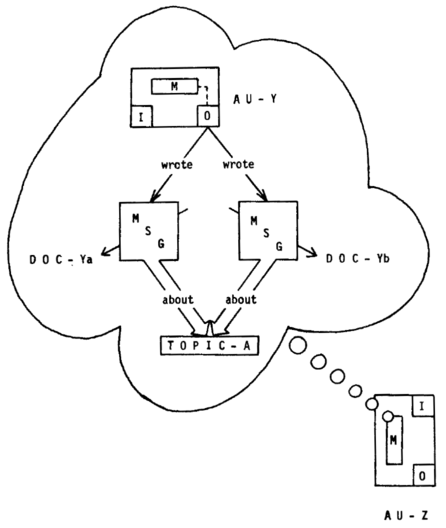

In figure 5c I have indicated that DOC-X contains text about TOPIC-A,

TOPIC-C, TOPIC-E, and TOPIC-F. I could have shown an example with the

same topic list for DOC-X as in DOC-Y. Indeed, different authors sometimes

write about the same kinds of things in much the same way, perhaps making

just some fine distinction between them, a distinction unimportant to

general subject indexing but perhaps very important to the researcher.

However, authors also write their own messages about the world and often

include only some of the same topics that someone else has covered in a

document they have read. The resulting dispersal of topics may cause

scatter headaches for the librarian who likes to keep every topic neatly

filed, but such a state of affairs cannot be avoided without a stifling

regimentation of research.

I symbolize different topics for the two documents in 5a, b, and c,

as I believe that case is more typical than completely co-extensive

documents, or at least so it might seem to a researcher who is not required —

as is the indexer as part of his job — to say in a few short statements

what the topic of a given document is. What the researcher does when he

authors an document is say what he wants to say about whatever topics he

is currently writing up. In doing so he may make reference to previous

work in the same area, more or less well defined.

When a reader uses DOC-X, he will not necessarily find TOPIC-A

covered first, then TOPIC-C, next TOPIC-E and finally TOPIC-F. He will

no doubt find a coherent text that might or might not be separable into

sections relating to those topics. Nonetheless, if DOC-X is related to

DOC-Y through inclusion of material about TOPIC-A, then when the portion

of the message of DOC-X is more or less about TOPIC-A, there might well be

explicit locational reference to DOC-Y, and not just to ways of finding the

general location of the document, but also, in many professional scholarly styles,

to the specific portions of DOC-Y that refer to TOPIC-A, although the style

and extensiveness of citation varies from author to author, from academic

discipline to academic discipline, from journal to journal, and from publisher

to publisher.

Primary document reference can be more valuable than the usual

general subject index reference for someone interested in reading about

TOPIC-A because it includes textual reference to TOPIC-A in two documents

that include discussion of the topic in and among discussion, on the one

hand, in DOC-X of figure 5c, of TOPIC-C, TOPIC-E, and TOPIC-F, and on the

other hand, in DOC-Y, among discussion of TOPIC-B, TOPIC-C again, and

TOPIC-D. Because of the nature of the texts of researched academic

messages, all of these topics are probably well related in one way or another.

Finding topics discussed this way in st least two documents will probably

help the researching reader zero in on TOPIC-A from a wider standpoint

than the simpler-minded, 'What are the facts about TOPIC-A?'

Furthermore, because researched articles usually contain reference to

more than one other document, a whole network of citations related in some

way to TOPIC-A may open up to the reader who stumbles upon or is directed

to at least one such document. Such a network of citations is what makes

the citation indexes from Philadelphia work for the researcher, about

which topic more below. Citations only work, however, for the document

user who is interested in following up on and reading whatever references

are made by the document's author. Not all other works cited will be

directly useful, but they will at least help provide an understanding of

what point the author doing the citing is trying to make. Understanding

the background of an author's claims so that an evaluative judgment can

be made is a key aspect of critical research. Critical research involves

much more than the fact finding that a popular view of science seems to

hold as representative of scientific research.

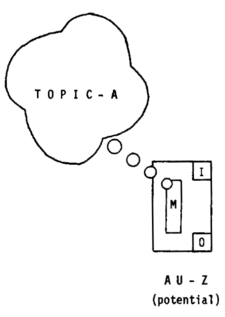

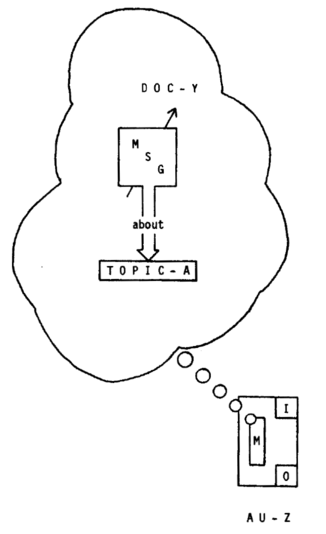

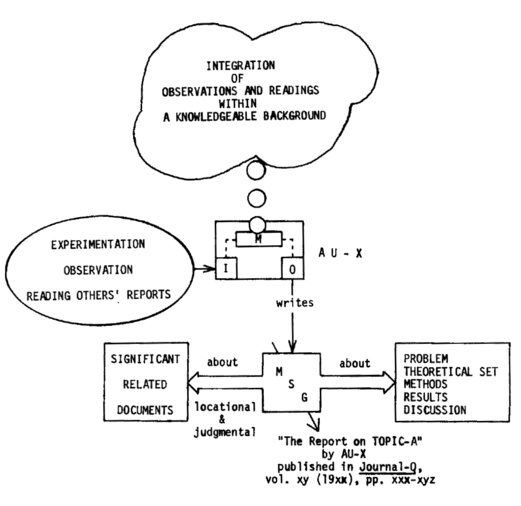

Now suppose again that we have a person searching for some material on

TOPIC-A. We can symbolize this person as in figure 6, where I have tried

to indicate through use of a conventional cartoon device that this person

has TOPIC-A more or less in mind. How he got to that hazy condition is a

fact of his life. This person is now wanting to find something he can

read about TOPIC-A, that is, he wants to make connection to his IN-sensors

that will bring some information to process inside his mind along with his

foggy notion about TOPIC-A. I assume further that this person, after

reading about TOPIC-A, intends to, or is required to, if possible, control

his OUT-organs and create a message potentially for storage, which will come

to be known as DOC-Z. It is for this reason that I have labelled the

personal symbol in figure 6 AU-Z (potential).

If this person is unfamiliar with the primary literature concerning

TOPIC-A, he may go to a subject index, which he perhaps views at this point

as a static device as in figure 3, scan its list of subject statement entries,

and, assuming he can match his more or less foggy notion of TOPIC-A with

some entry on the list, be led by the index to DOC-Y. When this searcher

gets to DOC-Y, he will then have the problem of finding relevant discussion

of TOPIC-A, which, depending on the topic and the document, may be more or

less easy to do, as discussed above.

This same person symbolized in figure 6 may have come across DOC-X,

perhaps by accident in the current periodicals section of a library, in

which case it may well not be indexed in a standard index yet, or he may

get to DOC-X through other means, conventional or non-conventional, including

even perhaps through a subject index in the manner described above, if

enough time has elapsed since DOC-X was published, if it was published.

No matter how he gets to DOC-X, as symbolized in figure 5c, there he will

find a citation to DOC-Y much like what he found also in the subject index,

i.e. with indication as to where to locate DOC-Y. He will also probably

find in DOC-X a wider discussion than what might be narrowly associated with

TOPIC-A (as discussed in the previous section in connection with figure 5c).

Now if potential AU-Z is conducting research, which may include fact

finding but also requires more thinking, he will probably appreciate and

benefit from the discussion of TOPIC-A that he finds in DOC-X. He may

disagree or agree with AU-X, but at any rate he should appreciate having

reference to another text created by another author concerned with TOPIC-A.

Indeed, if this person were conducting only a fact finding search, he may

be satisfied with what he finds in DOC-X and not wish to look further into

DOC-Y except perhaps to see whether AU-Y agrees with AU-X, something he may

already know from having read DOC-X's judgmental reference to DOC-Y.

Checking back on cited sources is a rather basic aspect of research

which graduate students are normally expected to know about. Again Morton

Fried's guide to the study of anthropology states this aspect well. In a

discussion of the evaluation of papers written by prospective graduate

students, Fried says,

. . . there is increased expectation that statements will not be

taken as fact simply because they appear in print. Graduate papers

should display a critical attitude toward the information used; they

should reveal the interest of the student in the methods used to obtain

the original data, and some curiosity about the logical tools employed

in manipulating them. One expects to find an awareness of theoretical

sets, whether apparent or latent. In other words, graduate students,

much more than undergraduates, must show sophistication in assessing

the biases that produced the work on which their papers rely. [Fried

digresses briefly to assert that undergraduates also can make critical

judgments, and then he continues.] One way of accomplishing this, as

suggested earlier [cited above], is to do research [emphasis Fried's]

on the critical statements found in the work of others that supplies

the main basis of the paper in question. This means digging into

learned journals to find reviews or critiques of that work, checking

out the author's sources, trying to find other accounts of the same

phenomenon. Even if the student lacks the expertise needed to make

an authoritative decision about truth, it is possible to indicate

the basis for acceptance or rejection of the statements in concern.

[18, pp. 196–197]

What Fried is describing is partly the rites of passage from student

to researcher, perhaps also from searcher to researcher. It is no linguistic

coincidence that one way a person can come to be considered an authority

is to author something. To become a published author, one has to accept

careful scrutiny of the text of a message one wishes to send to the world.

Part of this scrutiny one does himself as a part of the research in preparation

for formulation of the final text. The checking and verifying described by

Fried is an essential part of that research. Researchers may use a subject

index as a guide to that research, but usually, I believe, only, if at all,

in the early stages of research for getting started and perhaps then later

to do some looking anew at the topic of research in an attempt, as Fried

says, "to find other accounts of the same phenomenon" after already having

formulated a definite opinion.

Both the researcher and the indexer must read and understand the

message of a document they are dealing with in order to be able to fulfill

their professional tasks, allowing, of course, for the normal misunderstanding

that occurs in the course of human events. But what the researcher and the

indexer each does with the understanding of a text are quite different

things. This difference is stated well in a philosophical tradition concerning

the understanding of what philosophers like to call the proposition of a

statement, what we might call the 'aboutness' of the message texts in our

context. The philosopher G. E. Moore made a three way distinction in what

a person can do after understanding a proposition — believe it; disbelieve

it; or neither believe nor disbelieve but simply understand it. [24, p. 56]

The researcher in the present analysis has at least the first two

options and may even exercise the third, suspending judgment until further

research can allow him to make an evaluation.

The indexer's professional role allows him only the third option.

His task is to construct a device to point accurately and meaningfully to

whatever document he is indexing. As a critical person, the indexer may

exercise either of the belief options, but his professional duty requires

him to create a simple message that fairly represents the contents of the

document's message text through his understanding of that message.

It may well be that an indexer with a less personally committed view

of a text can perform a more efficient job of simply understanding the

text and representing it with general subject statement indicators than can

a committed researcher. That is to say, subject experts may not be detached

enough from a field to make the simple understanding required in indexing.

I do not mean simple here in any pejorative sense, because having to do a

quick read of a long or short, more or less dense text and then come up

with a short statement or series of statements giving good indication of

the contents of that text is not a simple task. The simplicity is even

less apparent when one realizes that an indexer performs such a task on

several texts each working day for perhaps many years. The individual

task with each text is just less complex for the indexer than for the

researcher who must make that text and its contents fit into everything

else he knows about the perhaps very narrow TOPIC-A. The latter requirement

is the critical review which is a part of the research process.

Librarians who deal with documents as individual item are less aware

of the internal connections because of the lack of a requirement to deal

professionally as believing or disbelieving whatever is contained in the

text of the document's message. Such detachment from the contents of a

text leads, I feel, to the view of the inherent separability of text and

references that I criticized at the outset. The uncritical attitude is

carried to an extreme when librarians and other information handlers worry

that citations may be to other works that an author wishes to refute, thus,

I guess, making the information handler's analysis of citation practices

less than an ever upward, positive and progressive view of the development

of knowledge. [12, p. 309]

I sense among librarians an attitude toward written works that is

reminiscent again of Fried's description of the undergraduate student

who has not as yet developed critical abilities, and perhaps never will:

Students sometimes take the position that a paper deserves the optimum